Slaying Dragons and Exploring Digital Dungeons: The Dawn of Computer Adventures in the Early 1980s

When gamers picked up the March 1982 issue of Electronic Games Magazine, they were stepping into more than just another issue filled with arcade scores and joystick reviews. They were opening a window into the birth of computer-based role-playing games (RPGs), a frontier where imagination, technology, and storytelling collided. In this issue, Arnie Katz’s article “An Introduction to Computer Adventures” explored how the digital world was beginning to mirror the dice rolls, character sheets, and dungeon masters of Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) — but on a glowing screen instead of a tabletop.

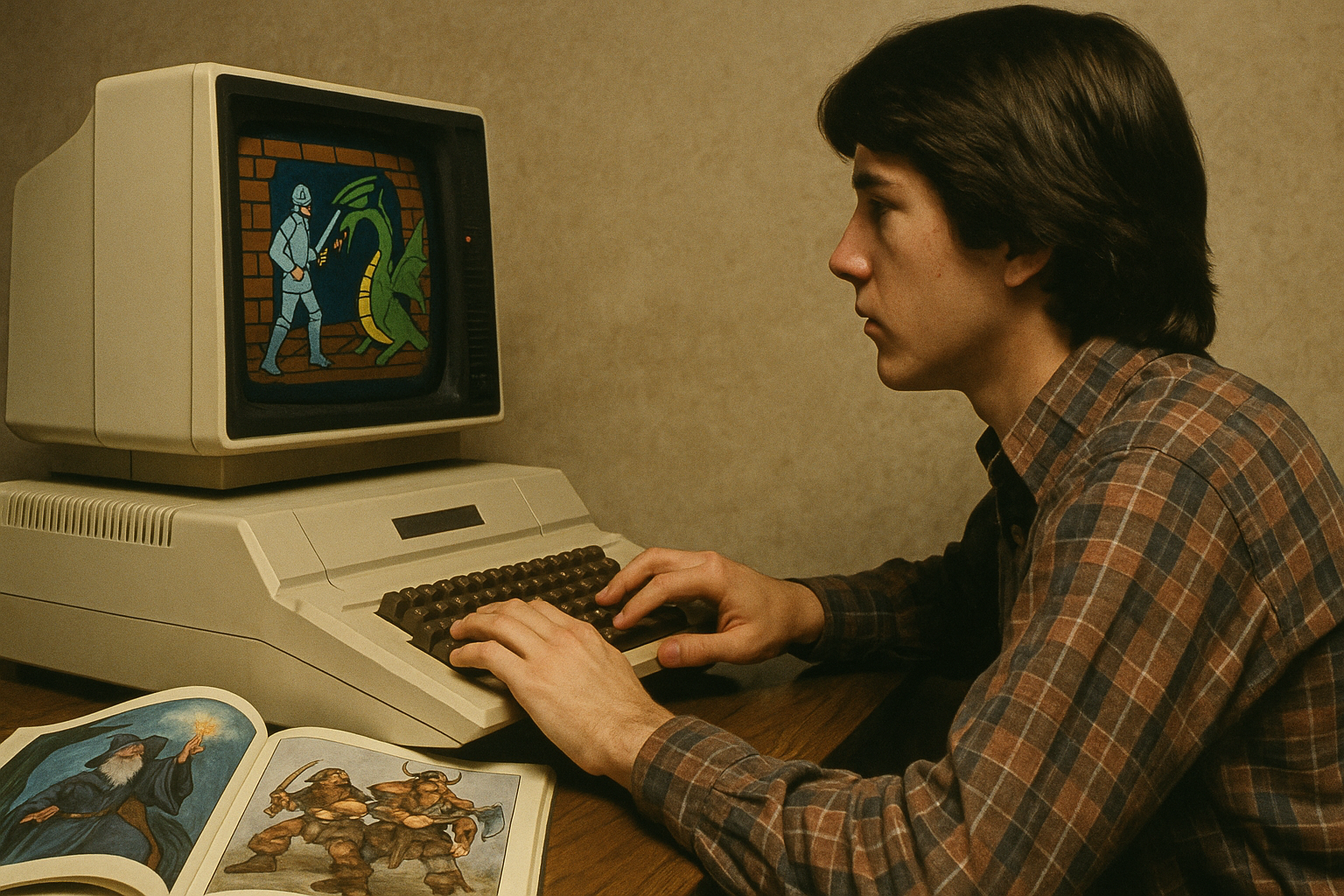

For readers in 1982, this wasn’t just entertainment. It was an early look at how computers could transform storytelling and gaming, blending the narrative complexity of fantasy adventures with the interactive thrill of programming and personal computing. With the rise of home computers like the Apple II, TRS-80, and Atari 400/800, the idea that a machine could generate quests, treasures, and monsters was both revolutionary and irresistible.

The early 1980s were a time of massive growth in video gaming culture. Arcades were booming, with classics like Pac-Man, Defender, and Donkey Kong devouring quarters across America. At the same time, home consoles such as the Atari 2600 and Intellivision brought electronic gaming into living rooms. Yet, a parallel revolution was unfolding quietly on personal computers.

Unlike arcade titles, which emphasized reflexes and high scores, computer adventures focused on storytelling, character development, and imagination. The influence of tabletop RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons was clear — the concept of a dungeon master guiding players through perilous quests inspired programmers to create digital equivalents. Katz’s article described this evolution in detail, showing readers how their new personal computers could become portals to fantasy worlds.

This was significant for two reasons:

-

It showed that video games could be more than action and reflexes — they could tell stories.

-

It revealed how home computing and gaming were merging, foreshadowing the RPG and adventure genres that would later dominate the industry.

At the time, this was groundbreaking. Just as arcades symbolized social fun, computer adventures symbolized personal immersion — a one-on-one experience between the player and the machine.

By 1982, Electronic Games Magazine had already established itself as the first major publication dedicated entirely to video games. Unlike general-interest magazines, EG treated games as a serious cultural and technological movement. The March 1982 issue was no exception.

The Cover: A Decade of Programmable Videogames

The bold cover featured a towering stack of quarters, a symbol of the arcade economy, surrounded by colorful characters from popular titles. It was both playful and symbolic — a nod to the cost of gaming and the anniversary of ten years of programmable video games. This wasn’t just about machines; it was about a growing culture of play, money, and imagination.

The Adventure Feature

Inside, Katz’s article introduced readers to five distinct types of computer adventures:

-

Text Adventures – Games like Adventure or Zork, where typed commands controlled the action.

-

Augmented Text Adventures – Standard adventures with added audiovisual elements, like simple graphics or sounds.

-

Illustrated Adventures – Titles that included visual depictions of locations or characters.

-

Action Adventures – Games that emphasized dexterity and movement, blending arcade action with adventure narratives.

-

Graphics Adventures – More advanced games offering detailed visuals, closer to traditional RPGs.

This breakdown helped readers understand not only what was available but also how the genre was evolving in real time.

The Visuals

The pages were decorated with fantasy-themed illustrations: a wizard casting spells, a dwarf with an axe, a cloaked cleric, and a Viking warrior. These visuals captured the spirit of early RPGs and showed how the magazine embraced both the fantasy tradition of tabletop gaming and its digital future.

-

From Dice to Disks – Katz explained how computer adventures substituted programming for a human Dungeon Master, opening the door to solo play and infinite replayability.

-

Necessity Breeds Innovation – Early programmers, constrained by limited memory and processing power, created ingenious ways to simulate fantasy worlds.

-

The Five Types of Adventures – By categorizing adventure games, Katz gave readers a roadmap to navigate this new genre.

-

Bridging Fantasy and Technology – The article highlighted how computer adventures tapped into the same imaginative spirit as D&D, but with the added magic of electronics.

-

The Human Element – While games could automate a Dungeon Master’s role, Katz acknowledged that no program could yet match the creativity of a live storyteller.

Together, these insights reflected a cultural turning point: video games were no longer just about chasing high scores — they were about living stories.

For collectors of vintage gaming magazines, the March 1982 issue of Electronic Games is a treasure. Here’s why:

-

Historical Timing – Published at the height of the arcade boom and the dawn of computer RPGs, it captures a unique transitional moment.

-

Iconic Cover – The stacked quarters cover is instantly recognizable and symbolic of the arcade era.

-

Pioneering RPG Coverage – Katz’s article was among the earliest mainstream discussions of computer adventures, making it historically significant.

-

Collector Demand – Early Electronic Games issues are highly sought after by retro gamers, historians, and fans of the 1980s arcade/computer boom.

Owning this issue isn’t just about nostalgia. It’s about holding an artifact of gaming history — a printed record of how video games evolved from reflex-based entertainment to immersive storytelling.

The genius of Electronic Games Magazine was that it treated video games with the seriousness of any other art form or cultural phenomenon. It didn’t dismiss games as toys. Instead, it analyzed them, celebrated them, and documented their rise as a global industry.

Without magazines like this, much of the early history of gaming would be lost. Today, revisiting these issues shows us not only how games looked and played in 1982 but also how people thought about them — their hopes, their concerns, and their visions for the future.

If you’re a fan of vintage computing or the early days of role-playing games, this issue is essential. It captures a pivotal moment when fantasy and technology merged, and it remains just as fascinating to read today as it was in 1982.

👉 Browse the full collection of original Electronic Games magazines here:

Original Electronic Games Collection

Whether you’re a seasoned collector, a retro gamer, or a historian of digital culture, Electronic Games magazines offer something special: the chance to relive gaming history as it first unfolded.

The March 1982 issue of Electronic Games Magazine stands as one of the most important early documents of gaming culture. With its feature on computer adventures, it showed how games could move beyond the arcade and into deeper, story-driven experiences. It also demonstrated the magazine’s role as a pioneer, setting the tone for all future gaming journalism.

Holding this issue today is like holding a map of gaming’s future, drawn at a time when the path was still uncertain but full of promise. It reminds us that from slaying dragons in D&D to exploring dungeons on floppy disks, the human desire for stories and play is eternal — only the medium changes.

For anyone who values the history of gaming, vintage magazines like this aren’t just collectibles. They are time machines, letting us see how the world of electronic adventures was imagined, described, and celebrated at the dawn of the 1980s.