Ancient China Under Siege: Peiping’s Monuments, the Japanese Invasion, and Life Magazine’s Lens in 1937

When readers opened the August 23, 1937 issue of Life Magazine, they stepped into the heart of China at one of its most perilous moments. The feature on Peiping—modern-day Beijing—captured a city of imperial splendor, layered with centuries of dynastic history, just as it fell under Japanese military occupation in the early months of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

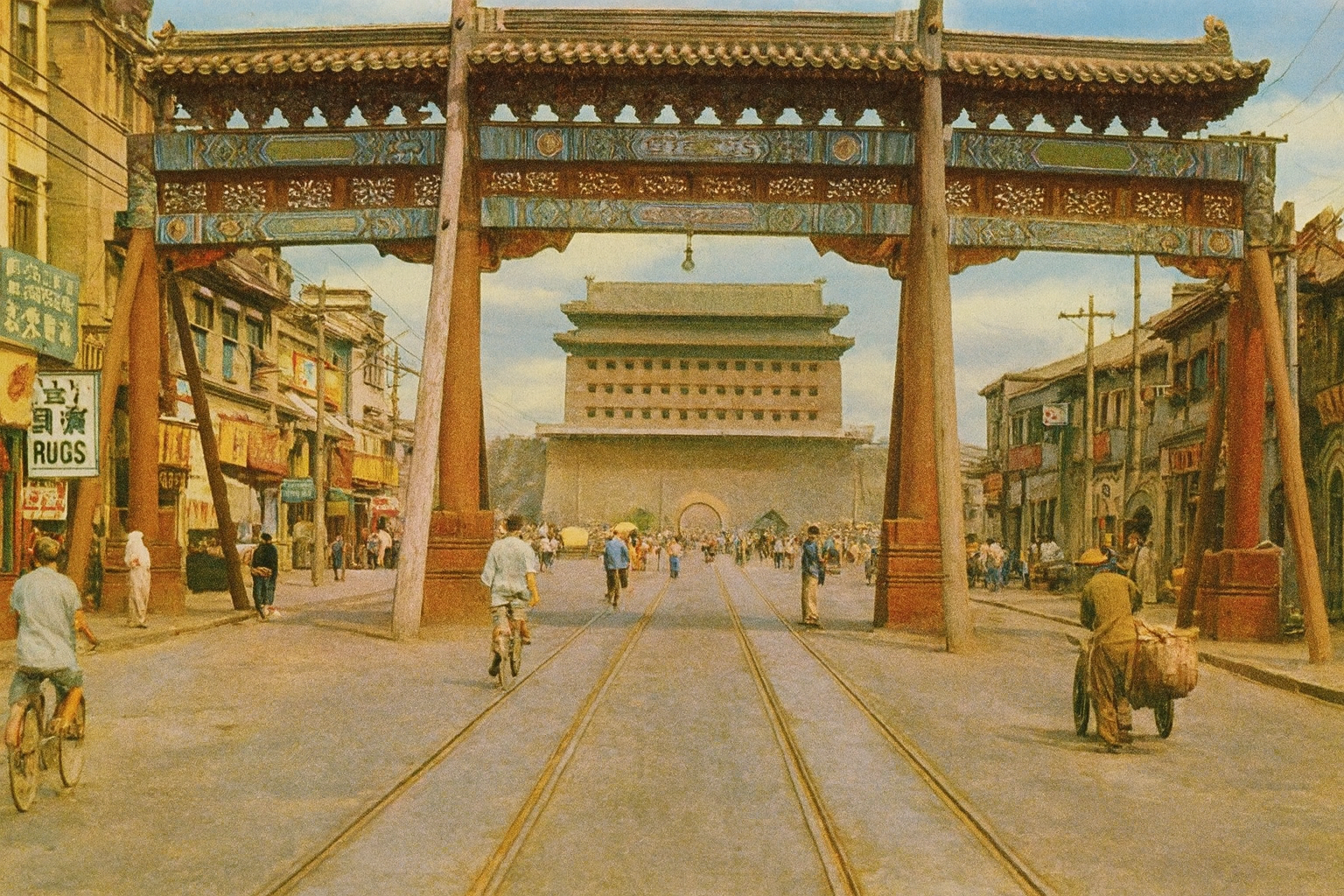

This was not just travel writing or cultural observation. It was history being reported in real time. The photographs showed iconic sites like the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace, the Ming Tombs, and the Great Wall of China—timeless symbols of Chinese power—alongside descriptions of Japanese forces pressing their advance. For American readers in 1937, this article was an education in both China’s deep heritage and its fragile modern predicament.

The summer of 1937 marked a turning point in East Asia. On July 7, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident near Peiping triggered full-scale war between China and Japan. Within weeks, Japanese divisions were advancing across North China, targeting Beijing (then often referred to in English as Peiping) as a strategic prize.

Life Magazine’s coverage appeared just two weeks after Japanese troops under General Masakazu Kawabe occupied the city on August 8. At the time, many Americans had little awareness of China beyond exotic stereotypes. This feature provided readers with a rare, vivid look at the monuments and landmarks that defined the country’s cultural identity—while also showing how those very places were being overshadowed by modern conflict.

The article contextualized Peiping as more than just a modern city of 1.4 million people. It traced its history back centuries, from the Mongol conquest of Kublai Khan in the 13th century, through the Ming dynasty’s expansion, to the Qing dynasty’s final collapse in 1911. By 1937, Peiping was both a living capital of Chinese tradition and a battleground for control of China’s future.

For readers in the United States, these photographs and essays provided more than a lesson in Chinese history. They revealed the fragility of cultural treasures in wartime and offered an early glimpse into a conflict that would, just four years later, merge into World War II on a global scale.

The genius of Life Magazine in the 1930s lay in its ability to blend narrative text with striking photojournalism. Unlike other publications of the time, Life believed photographs could tell a story just as powerfully as words. The August 23, 1937 issue was a perfect example.

Readers saw panoramic spreads of Peiping’s Summer Palace, with its lotus-covered lakes, ornate pavilions, and the dragon throne of the Empress Dowager Tzu Hsi. They saw the solemn stone sentinels of the Ming Tombs, standing guard over emperors long dead, as Japanese divisions marched past. They saw the sinuous curves of the Great Wall, photographed in breathtaking detail as it wound through the mountains.

Equally compelling were images of the Forbidden City, with its gilded roofs and ceremonial halls. In 1937, this was not yet a tourist attraction—it was still a functioning symbol of imperial China, only recently repurposed by the Republic. The juxtaposition of these ancient monuments with descriptions of Japanese troops advancing across the plains made the article a powerful reminder of how history and war collide.

Life’s reporting did something few publications could: it made the distant tangible. American readers could almost feel the weight of history pressing down on Peiping, even as the modern world reshaped it.

The August 23, 1937 issue featured a striking cover image of a transoceanic transport plane—fitting for a world increasingly connected by both technology and conflict. While the cover itself focused on aviation, the Peiping feature inside embodied Life’s hallmark style: bold, black-and-white photographs paired with clear, explanatory captions and concise but authoritative narrative.

Unlike illustrated magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, Life rejected idealized art in favor of realism. Its editors believed Americans needed to see the world as it was, whether that meant the faces of Depression-era workers, the destruction of Spain’s civil war, or the splendor and fragility of China’s monuments.

The Peiping photo-essay exemplified this. Each spread combined sweeping landscapes with intimate details—ornamental tiles, carved stone statues, and crowded city streets. Captions didn’t just identify subjects; they contextualized them, explaining the history of each site while noting its relevance in the present war.

This blend of immediacy and permanence was Life’s great innovation. It allowed readers to move seamlessly from timeless cultural heritage to breaking geopolitical events, all within a few pages.

-

The Summer Palace: Begun in 1889 by Empress Tzu Hsi, the Summer Palace was presented as both a monument to imperial extravagance and a symbol of cultural endurance. Its “Mountain of 10,000 Ages” and lotus-filled lake made it one of China’s most picturesque landmarks.

-

The Empress Dowager Tzu Hsi: The article highlighted her as one of the most dominant figures in modern Chinese history, ruling for nearly half a century and shaping the palace in her image.

-

The Ming Tombs: The statues of camels, horses, and warriors lining the road to the tombs illustrated the grandeur of China’s imperial burial traditions, while Life pointedly noted that Japanese forces were now encamped nearby.

-

The Great Wall: Described as stretching 1,500 miles, with watchtowers every 600 feet, the Wall symbolized China’s resilience against centuries of invasion, even as it was again tested in 1937.

-

The Forbidden City: With aerial and ground photographs, Life captured the splendor of the palace complex, including the Temple of Heaven and the Dragon Wall, reminders of China’s dynastic continuity.

-

The Japanese Invasion: Most powerfully, the issue documented how ancient heritage sites now lay in the path of advancing armies, making cultural destruction a looming reality.

For collectors today, Life magazine August 23, 1937 is not just a vintage periodical—it is a historical artifact.

Why is this issue so collectible?

-

Timing: Published just weeks after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, it captures one of the first major episodes of the conflict that would expand into World War II.

-

Iconic Photography: The images of Peiping’s monuments remain some of the most striking visual records of these sites before decades of war and modernization changed them forever.

-

Cultural Significance: This issue bridges the gap between China’s dynastic past and its modern struggle for survival, offering a snapshot of a nation on the brink of transformation.

-

Collector Demand: Vintage Life magazines from the 1930s are especially sought after, and milestone issues tied to major world events—such as this one—are prized by history buffs, educators, and families seeking tangible links to the past.

Owning this issue is like holding a piece of 20th-century history. It carries the immediacy of breaking news from 1937 and the timeless resonance of ancient Chinese heritage.

Part of the enduring appeal of Life’s 1930s and 1940s issues is their dual nature. They are at once news reports of their day and carefully composed visual histories. For readers then, they offered the only way to see beyond America’s borders. For readers now, they are time capsules—original artifacts that let us revisit the world as it was first experienced.

Unlike today’s fleeting digital images, these printed pages were meant to be studied, passed around, and saved. Families kept Life issues on coffee tables, schools used them for teaching, and collectors now prize them as physical witnesses to history.

That’s why vintage Life magazines remain highly collectible today. They are not just reading material; they are living artifacts, complete with the original ads, captions, and photographs that shaped mid-20th-century consciousness.

If you’re fascinated by this issue, you’ll be glad to know it’s just one among thousands of vintage Life magazines that have survived. From the 1930s through the 1970s, Life chronicled everything from wars and politics to fashion, science, and pop culture.

👉 Browse the full collection of original Life magazines here: Original Life Magazines Collection.

Whether you’re a seasoned collector, a student of history, or someone honoring the memory of relatives who lived through this era, these magazines offer something special: the ability to see history as it was first reported, in the very pages your grandparents might have turned.

The August 23, 1937 issue of Life Magazine remains a powerful document of both cultural heritage and global crisis. By showcasing Peiping’s Summer Palace, Ming Tombs, Great Wall, and Forbidden City at the exact moment Japanese forces were advancing, it preserved a moment when the weight of centuries met the violence of modern war.

For historians, collectors, and anyone curious about how Americans first understood China in the 1930s, this issue is invaluable. Its photographs are not only records of architecture and monuments but also symbols of resilience amid upheaval.

Holding this issue today is to hold a piece of history—when Life brought the ancient and the modern, the beautiful and the tragic, into American homes in a way no other publication could.